We've put this update together a little earlier than scheduled in light of events over the last couple of weeks which have been leading financial (and indeed many mainstream) headlines. As you will have probably already seen, after a sustained period of negative news stories and despite a brief rally in its shares following the announcement of a $54bn lifeline from the Swiss National Bank, Credit Suisse has been bought by UBS for $3.25bn. Swiss regulators brokered the sale in order to shore up the country’s banking system to try to reduce the contagion risk spreading to other companies.

Whilst the crisis peaked last week, the bank’s demise had been a long time in the making. Scandals ranged from losing their CEO following corporate spying allegations to financial hits from writing off bad loans to the likes of Greensill Capital and culminated in the firm admitting last week that it had found “material weaknesses” in its financial reporting. As one analyst put it, “they managed to be front and centre in almost every corporate mishap or scandal of the last decade”. Prior to its sale, the share price had fallen by 99% from the peak it hit in 2007.

Credit Suisse – an ignominious end

Source: koyfin.com, Credit Suisse share price since 2007-peak

Given all of this it is fairer to say that Credit Suisse is the architect of its own destruction rather than a canary in the coalmine for problems in the wider banking sector. Nevertheless other banks experienced share price falls, largely because fear is a powerful motivator; no-one wants to be the last to sell in the event that the ripples spread further out. The good news is that despite calls for lower regulation from policy makers with short memories, the banking system is in a much better position than it was in 2008/9 thanks to requirements for greater liquidity and segregation of assets that were imposed in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis.

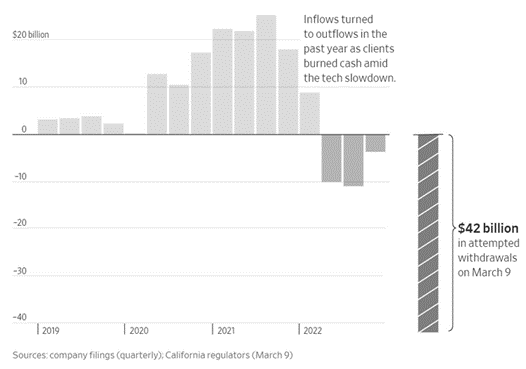

The weekend sale of Credit Suisse mirrored (albeit on a much larger scale) the purchase of the UK subsidiary of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) by HSBC the weekend before which was triggered by the failure of its parent company. SVB, as the name suggests, focused on nascent tech and healthcare companies in the US. It was America’s 16th largest bank but (along with a couple of other small, crypto-focused banks) represented only a tiny fraction of the $23tn US banking sector. It came under pressure as its clients, many of which have themselves been feeling the strain of tighter market conditions, pulled out billions of dollars, including over 25% of their total deposits in one day, and the bank struggled to give them back their money.

Silicon Valley Bank’s outflows

Source: as noted

The main reason for this was the failure of the symbiotic relationship between the bank and its clients. These companies used SVB to hold the vast sums they received from their investors and were less reliant on borrowing money to fund their growth. As a result, SVB invested in US Treasuries as a way of making a “safe” profit while paying a competitive interest rate to the savvy companies on their books. This worked perfectly well until the decade of cheap money ended as central banks started to put up interest rates which simultaneously caused bond prices to crash (as we’ve covered previously).

As SVB’s clients started to drain their accounts as their own funding evaporated, the bank was forced to sell its government bond assets at a loss and as other clients realised this (inevitably, given the close relationships between the firms), withdrawal requests became a full-scale bank run. Regulators in the US quickly said that SVB’s depositors would be fully repaid (which was necessary as some 96% of them were not covered by a compensation scheme) but as yet they have failed to secure a buyer for the bank’s assets.

Silicon Valley Bank’s uninsured clients

Source: as noted

With the fallout from the collapse continuing to impact on other small institutions in the US, it’s worth saying that the two overlapping bank crises are almost entirely unconnected – SVB failed because it wasn’t subject to the same regulatory oversight of the larger, “too big to fail” banks and it exposed itself to a perfect storm of an overreliance on US government debt and a highly undiversified and flighty customer-base while Credit Suisse was a basket case of bad management. The problem is that the proximity of the two events has the effect of tainting the entire industry.

As a result, regulators and institutions from the US to Asia have been moving to reassure investors that the crisis can be contained. The vice president of the European Central Bank (ECB) has described the EU banking sector as “resilient”, the Bank of England (BoE) have said ours is well capitalised and well funded and the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) Janet Yellen has said hers is “sound”. Meanwhile the 11 largest US banks stepped in to provide $30bn in support to First Republic, one of the banks that has struggled following SVB’s collapse, and the Fed have also joined forces with five other major central banks to increase liquidity by switching from weekly to daily Dollar auctions; however, in a positive, sign, there has been very little interest in the scheme.

So, what happens next? One immediate impact was on forecasts for interest rates - markets had previously baked in a half percent rise from the Fed but it was then faced with finding a balance between controlling inflation without causing further issues for the banking sector. Do too much and markets get spooked and growth falters, do too little and inflation persists and growth falters.

Yesterday it was confirmed that it had opted for a more traditional 0.25% rise with the announcement being couched in very conservative language. Part of the Fed’s thinking will be that credit conditions will tighten following SVB’s failure, which itself will act as a brake on growth. Elsewhere, UK inflation unexpectedly rose from 10.1% to 10.4% in February which added to the BoE’s headache about what to do about interest rates. As is usually the case, today they followed the lead set by the Fed with a 0.25% rise.

In Europe, having all but guaranteed a large rise at their previous meeting, the ECB pressed ahead with a 0.5% rise to take its benchmark deposit rate to 3%. There were understandably some dissenting voices, but clearly the consensus was that bringing inflation down should remain the priority. This view is shared by the OECD, an intergovernmental economic development organisation, which has urged the world’s central banks to stay the course as continuing labour market pressures could negate price falls in food and fuel.

This fast-moving situation continues to evolve so many of the points discussed above might already be out of date by the time you read this update. From a rational perspective, for all the reasons covered above, there is no reason to think that this will be more than a short-term bout of volatility, but sentiment is key and it would be naïve to assume that this will quickly blow over, especially if the corrective actions already taken fail to break the current “doom loop”. Hopefully calm heads will prevail, but either way, with the sharp and unpredictable market movements we’ve already experienced (both up and down), now is no time to be trying to predict what will happen next.

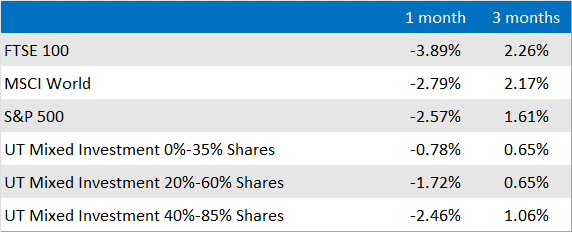

Market and sector summary to 22nd March 2023

Source: Financial Express Analytics.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance, nor a reliable indicator of future results or performance.